Scott Walters at Theatre Ideas has recently published a flurry of posts on the subject of decentralization of theatre funding.

Many bloggers have been commending Scott’s passionate research and arguing for the more equal distribution of theater funds. This is encouraging because, “it takes a village,” as the African proverb and Hillary say. If decentralization is to actually find traction, the notion will need as many cheerleaders as can be found. More importantly, the actual players up for this game will need to identify themselves and step onto the court.

Scott tells us he is meeting with a willing group of players in California this weekend. No doubt there are many more such groups across the country. During the ten years of the Rat Conference, we continually discussed and attempted to enact methods of decentralization. We succeeded in fits and starts. The story of how RAT, which began as a counter to the regional theatre system and representative of “regional alternative theatre,” became co-opted in large part into the existing TCG establishment would have a complex telling. However, the skinny of that story is that most theatre people are divided in their ambition. The inherent obscurity of producing theatre at the community level is a continuing challenge to one’s self-esteem and most theatre people are at least half desirous for recognition if not success by the yardsticks of the dominant culture in which we are all immersed.

Popularity, celebrity, and money are interdependent. Theatre at the local level can rarely achieve enough popularity and celebrity to sustain an ensemble financially except in large urban areas with already existing theatre audience. Even in large cities, theatre itself is already an alternative to more popular entertainments and difficult to sustain solely through box office — New York and its species of Broadway with its touring show being the exception. All other theatre needs some type of patronage to remain viable.

Scott’s argument against the NEA and its elite patronage is not a new one. Although the scandal generated around the NEA Four performers obscured the issue, Jesse Helms was making exactly the same argument thirty years ago. The national arts funding debacle stemming from the so-called cultural wars in the early ‘90’s resulted in the passing of a new Congressional law. This “decency” test on art went all the way to the Supreme Court where it was upheld.

Although the NEA Four performers’ funding had only amounted to a miniscule percentage of the agency’s budget, or an infinitesimal amount if compared to, say, the military budget, its mere existence allowed the NEA to become the scapegoat of government spending, literally and figuratively, the “indecent” pork barrel of the art elites.

Jesse Helms was campaigning against the word “piss” being next to the word “christ,” not against the actual artwork entitled Piss Christ. And he was campaigning against others’ pork barrel not his state’s own (the nation’s tobacco-subsidy program ended only in 2004) when he demanded the NEA peer panel be held accountable to Congressional oversight and a more equitable distribution of federal arts funding.

Scott Walters gives us the exact same argument once more. But maybe without the scandal of a chocolate smeared naked woman performer we can actually see the the amount of money we are talking about.

Meanwhile, the idea that our regional theatre ought to spread the wonder of the theatre throughout this nation is abandoned. The National Endowment for the Arts data makes clear how much it is being abandoned.

Follow the money has always been good advice for evaluating what is truly valued. In fiscal year 2006, the NEA gave theatre grants in the amount of $2,878,000.

As Scott suggests, if we actually follow the money to find out “what is truly valued” as theatre in America, we would need to compare that $2,878,000 with the budget for a single Broadway play. The roughly $20 million budget of “Young Frankenstein” with some audience members paying $450 for their orchestra seats identifies precisely what theatre this country values.

At the center of International Culture Lab’s inaugural project is a new play by Berlin-based playwright Andreas Jungwirth that examines how capitalism has infiltrated our most personal relationships. The realities surrounding the production of this play are also the subject of the project. Two different sets of artistic peers, two different cultures of theatre came together in a co-production that necessarily became a study of how funding for theatre is provided. William Osborne’s Marketplace of Ideas: But First, The Bill: Personal Commentary On American and European Cultural Funding excellently points out the main differences.

As an American who has lived in Europe for the last 24 years, I see on a daily basis how different the American and European economic systems are, and how deeply this affects the ways they produce, market and perceive art. America advocates supply-side economics, small government and free trade – all reflecting a belief that societies should minimize government expenditure and maximize deregulated, privatized global capitalism. Corporate freedom is considered a direct and analogous extension of personal freedom. Europeans, by contrast, hold to mixed economies with large social and cultural programs. Governmental spending often equals about half the GNP. Europeans argue that an unmitigated capitalism creates an isomorphic, corporate-dominated society with reduced individual and social options. Americans insist that privatization and the marketplace provide greater efficiency than governments. These two economic systems have created something of a cultural divide between Europeans and Americans.

Germany’s public arts funding, for example, allows the country to have 23 times more full-time symphony orchestras per capita than the United States, and approximately 28 times more full-time opera houses. In Europe, publicly funded cultural institutions are used to educate young people and this helps to maintain a high level of interest in the arts. In America, arts education faces constant cutbacks, which helps reduce interest.

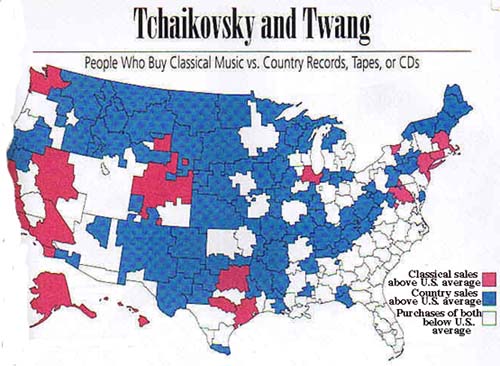

In making his argument Scott has painstakingly compiled a series of Google maps to show population density, TCG theaters and other such data. Scott’s collection of maps reminded me of an interesting book that entertained and informed much of the talk and many the collaborations between rat theatres and artists. Latitudes & Attitudes: An Atlas of American Tastes, Trends, Politics, and Passions by J. Weiss presents an amazing “nationwide consumer map with accompanying remarks on how Americans in various geographical areas feel about a particular food, drink, sport/leisure activity, household product, car, television show, music type, periodical, or political issue.” The various rat cities would have fun arguing pro or con the portrait their consumer habits presented. The maps in the book were an assortment of witty and often bizarre comparisons. I scanned the map below thinking that it would shed some light on one of the main problems in the distribution of the arts funding.

In a fantasy funding scenerio where Scott Walters was cultural czar and he was given the funding by Congress to establish the same per capita number of full-time symphony orchestras as Germany has, in what states and regions would he put them? How would he use the above map in making his decision? The figures quoted below from the same essay by William Osborne show us Cultural Czar Scott would have 465 new full-time, year-round orchestras to build.

International comparisons might illustrate this point. Germany, for example, has one full-time, year-round orchestra for every 590,000 people, while the United States has one for every 14 million (or 23 times less per capita.) Germany has about 80 year-round opera houses, while the U.S., with more than three times the population, does not have any. Even the Met only has a seven-month season. These numbers mean that larger German cities often have several orchestras. Munich has seven full-time, year-round professional orchestras, two full-time, year-round opera houses (one with a large resident ballet troupe,) as well as two full-time, large, spoken-word theaters for a population of only 1.2 million. Berlin has three full-time, year-round opera houses, though they may eventually have to close one due to the costs of rebuilding the city after reunification.

If America averaged the same ratios per capita as Germany, it would have 485 full-time, year-round orchestras instead of about 20. If New York City had the same number of orchestras per capita as Munich it would have about 45. If New York City had the same number of full-time operas as Berlin per capita it would have six. Areas such as Queens, Staten Island, and the Bronx would be nationally and internationally important cultural centers. The reality is somewhat different.

Even if the fantasy funding of this academic exercise were possible, Cultural Czar Scott would also have to decide whether or not it’s appropriate to fund symphonies and operas over country music. After all, wouldn’t the Czar then be imposing a culture and education onto a populace that prefers the Grand Ole Opry to the classics of Europe?

The paradox of the decentralization of theatre is that the voice in the Hollywood fantasy movie speaks the truth. “If you build it, they will come.” But in the celebrity culture of America, it would be best to have a movie star like Kevin Costner in your theatre ensemble.